425 Years of Stonyhurst College

- Alex Van Goethem

- Aug 26, 2019

- 7 min read

Updated: Jan 24, 2022

The closing of the 2018/9 academic year marks exactly 425 years since the creation of Stonyhurst College and its predecessors, and the beginning of its 225th year located in England, both occasions which the Jesuits in Britain Archives wishes to celebrate.

This article hopes to delve deeper into the fascinating history of the College by looking at the journey that led the College to be at Stonyhurst and exhibiting some of the items that our archives hold.

As many know, the College’s earliest predecessor was created following the enforcement of various statutes by Queen Elizabeth’s Government which hoped to suppress Catholicism in England, hence the decision to locate the English College not in England, but in Saint-Omer, France. The choice of Saint-Omer in particular, which at the time was part of Spanish Netherlands, was most likely made by Fr Robert Persons SJ because of its proximity to England and it being, along with Louvain and Douay, one of the most frequented towns by Catholic exiles. Spain’s King Phillip II’s sympathies for the sad plight of English Catholics led to a royal letter dated 13 March 1593, granting a yearly sum of 1,920 crowns for the proposed school, the King of Spain’s patronage continued to help the College grow in its infancy.[1]

Education at St Omer’s followed the usual courses taught at other Jesuit Colleges on the continent. This consisted of five or six ‘schools’ or classes, forming a graded hierarchy, each class with its definite objective to be attained before the pupil could advance further. The division of classes was more often determined by the subject studied rather than the proficiency of the students, and often classes would dovetail into the next so as to form part of a predetermined and unified system.[2]

Relative calm followed until 1636 when France declared war with Spain. Catholic France invaded and eventually regained the province home to St Omer’s, though St Omer’s remained largely unaffected the English Civil War, which followed in the 1640’s, did lead to drastically declining number of boys at the College.

St Omer’s recovered from the turmoil of the 1640’s, regaining its numbers and continuing to grow until 1762, when a growing wave of anti-Jesuitism hit the College and the Society of Jesus in France. A proliferation of anti-Jesuit propaganda preceded a law passed in August 1762 forbidding the existence of the Society of Jesus in France. Luckily the Jesuits at St Omer knew of the proposals before the law had passed and due to this were able to arrange for the transfer of the College and its students to beyond France’s reach, in Bruges, part of the Austrian Netherlands.[3] Though the Jesuits had left, the College continued to function as a school for English boys and was run by the English secular clergy until 1793, when they too were driven out by the French. Letters found within our archive collection describe how life went on as usual for boys who chose to remain at St Omer’s:

It reads:

“After dinner we have an allowance of play till 9 o’clock: we then go to French school & stay till three; at three to Latin school; we come out of school at 4 & a half, in winter at 4 & a quarter & play for a quarter of an hour: then to study place, & stay till the quarter past 6: then to a chappel in the house, which they call the Angel Guardian’s Chappel; there are said the litanies of Jesus but on Thursday they say night prayers, because there is benediction in [last] prayer time; & on Saturdays, because they sing the litanies of our Lady of Loretto. In this chappel we stay a quarter of an hour, & one of the boys, when the litanies are finished, reads some life of a saint, or some spiritual book. At 6 & a half we go to supper, & then have the rest of the night to play till the half hour past 8, then go to church to night prayers, & after that go to bed.”

The many that did choose to follow their Jesuit masters were welcomed into Bruges with open arms, though future events would not allow them to settle for too long. Only 11 years after their escape to Bruges from St Omer’s, on 16 August 1773, Pope Clement XIV issued a Brief suppressing the Society of Jesus and its activities throughout the world. Commanded by this Brief the Austrian government in Flanders burst into the College and seized all in sight, holding them as prisoners within their very own walls. For three weeks the ‘inmates’ were interrogated and the buildings searched for any plans of escape. The former students of the College meanwhile were requested to stay in Bruges and continue their education at the College under new leadership. The boys however rejected their new leaders and rebelled until local soldiers and Dominicans were introduced to take over the task of keeping the boys under control. In the meantime parents had started withdrawing their boys back to England, whilst others escaped, until only 43 boys remained.[4] Due to its dwindling numbers the authorities declared it no longer worthwhile to maintain the College and officially closed it in the late autumn of 1773.

At this point it seemed there was little hope of a Jesuit college for English Catholic boys. Luckily though, opportunity presented itself in Liege. The Jesuit Seminary at Liege, which was as affected by the Brief of Pope Clement XIV as Bruges and other Jesuit communities, received a lucky break in the form of the Brief’s executor for the principality. The executor - Prince-Bishop Mgr de Velbruck, had a longstanding friendly relationship with the English community and though officially executing the Brief – announcing the suppression, freeing the religious from their vows, and absorbing the property – he wished not to disturb the house or its occupants, allowing them to stay, provided they wore the dress of a secular priest, and bade them to continue their work.[5] As news about this stroke of luck spread, more and more boys, both from England and the recently closed College in Bruges, made their way to Liege. In December 1773 the new College term began, under the new title of the ‘English Academy’, and was led by Fr John Howard SJ as Director of the new Academy.

Within three years the Academy had grown to 150 scholars.[6] As at St Omer’s there were six classes, from Rhetoric to Figures, and also one or two lower classes.[7] As the Society was now technically suppressed, all distinctively Jesuit celebrations and devotions were no longer performed. This did not however prevent the boys making their annual three days of ‘Recollection’ at the beginning of each school year.[8]

Once again the College would be uprooted from its position, and once again the cause would be the French. In 1794 France was actively at war with England and others, and in May of that year French forces had re-entered Belgium, after occupying it for a while in 1972-1793. By the time the French were marching toward Liege boys who lived nearby were sent home whilst the rest were secretly marched off to a house in Wyck, now a suburb in Maastricht, Netherlands, to weather the storm for a few days before returning to Liege.[9] It was not until roughly a fortnight before the French arrival on July 27th that the decision was finally made to transfer the College and its remaining contents and students to England. Thus the final journey begun, on 14th July 1794 towards England. Following the river Meuse on barges the group would stop at Maastricht for nine days, perhaps in the hope of being able to return to Liege, before continuing to Rotterdam where they transferred onto a boat to cross the Channel to England. The group, after some delay would eventual reach the completion of its great escape at an unoccupied Hall, originally built in 1592 and eventually passed down to Thomas Weld, a former student at the College in Bruges who generously offered the empty Hall to the Society. This Hall was of course Stonyhurst in Lancashire, England, and though it took a number of years for the College to get a proper footing, including initial financial struggles, it has now been home to the much-travelled College for a period of 225 year.

The recollections of Fr Frederick Turner SJ, a former student and master at Stonyhurst College who first entered the College in 1922, describe the charms of the College:

“..the first thing I want to say is that Stonyhurst is impressive; whether you see it in an afternoon in early autumn with the leaves catching the sunlight, or a late afternoon in November with the wind and rain, it will impress you. You may like it or not, but you will be impressed. You may see it for a day or a week or forty years, as a school boy who hated most of his time here, or an old boy whose memory has filtered out the less pleasant parts and left a somewhat sentimental residue. You will be impressed by its history – the Shireburns who built it, the years of exile in St Omers, the martyrs, the V.C’s; by the many beautiful things (and some very ugly pieces of piety) inside it, and by its setting.”

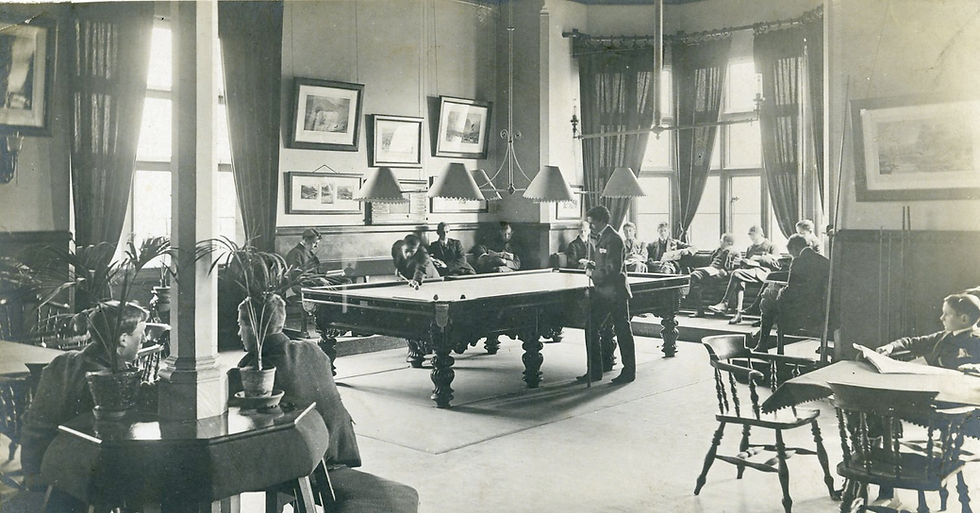

Starting with only roughly fifty boys the College at Stonyhurst has now grown exponentially to become one of the country’s leading Catholic independent schools, teaching a combined 745 boys and girls through its College and preparatory school St Mary’s Hall.[10] In May of 1881 the first issue of ‘The Stonyhurst Magazine’ was published, which, until 1935 continued to publish six issues per year but has since reduced to one. The contents of the magazine comprise of illustrated articles on both Stonyhurst’s past and present, and include reports on the year’s activities and news of former pupils. It is still published to this day, now known as ‘The Stonyhurst Association News’ newsletter.

Today the rich history of the College is treasured in the newly opened ‘Old Chapel Museum’, which lays claim to being the oldest museum collection in the English-speaking world. With its first acquisition dating back to 1609 its objects include: first folio of William Shakespeare; Prayer books belonging to Mary Queen of Scots and Elizabeth of York; manuscripts by Gerard Manley Hopkins, and many more, mostly donated to the museum through well-travelled Jesuit missionaries and former College students.

If you are interested in the history of the College or any of the items mentioned in this blog post, please contact us.

[1] Hubert Chadwick SJ St Omers to Stonyhurst 1962, p.12 [2] Hubert Chadwick SJ St Omers to Stonyhurst 1962 [3] “ p.312 [4] “ p.312 [5] Gruggen, G; Keating, J History of Stonyhurst College p.37 [6] “ p. 39 [7] Hubert Chadwick SJ St Omers to Stonyhurst 1962 p.364 [8] “ [9] The Story of the Migrations, Stonyhurst Magazine April 1952 [10] https://www.isc.co.uk/schools/england/lancashire/clitheroe/stonyhurst-college/

תגובות