Women in the Jesuit Rare Book Collection

- Lucy Vinten

- Feb 7, 2022

- 7 min read

The Jesuit collection of sixteenth and seventeenth century books is not an obvious place to look for women, but in a recent blog post I highlighted a book which had been owned and annotated by women before coming into the Jesuit collection. In this post I want to look at a few of the books from the collection which were printed by women.

In the seventeenth century the boundaries between publisher, printer and bookseller were indistinct but it is clear that these establishments tended to be small workshops, often family businesses with many members of a family involved in running them and perhaps a few employees as well. As such it is not surprising that women were involved in the business, but perhaps unexpected that at times women were named as the head of the business.

Of the nearly 200 pre 1700 books catalogued so far, 11 have a woman named as the printer. These are seven different individual women, and of them, six are only known to us by their husbands’ names. These six are all widows, and are identified on the title pages of the books they printed as ‘widow of Nicolas Courant’, ‘widow of Charles Boscard’ ‘widow of John Moretus’ and so on. I have not been able to trace the one woman whose own name is used on a title page – Anne Marie Vollmare of Würzburg.

I was interested in women printers of Catholic books, so had a look through the 507 books listed in Thomas H Clancy’s A Literary History of the English Jesuits, A century of Books 1615-1714. Of these, 22 have identifiably female printers, some of whom are the same individuals as the books in our collection and again all but one are not mentioned by name but as widows of their deceased printer-husbands.

All the women named as printers were widows, but in all likelihood they were business partners with their husbands during their husbands’ lifetimes and each one carried on the family business after their husband’s death. However, only when their husbands died did the women became visible on the title page.

The only female printer who was named by her own name on title pages of books listed by Clancy was Mary Thompson, who printed eight Jesuit books in 1688. Mary was wife then widow of printer Nathaniel Thompson and ran the printing business when he was first imprisoned and then died. Nathaniel had printed political works, as well as Catholic ones, whereas Mary printed exclusively Catholic ones, suggesting that she was making business decisions and taking the company in a different direction. Mary ran the business for eight years before handing it on to the next generation.

This pattern, of a named printer dying and the family printing company being run for a number of years by his widow until the next generation took over, is similar for all the books printed by widows. This appears to be the case in the Plantin Moretus printworks. Two different widows of this family company printed two of the books from the Jesuit collection, A/135 and A/138.

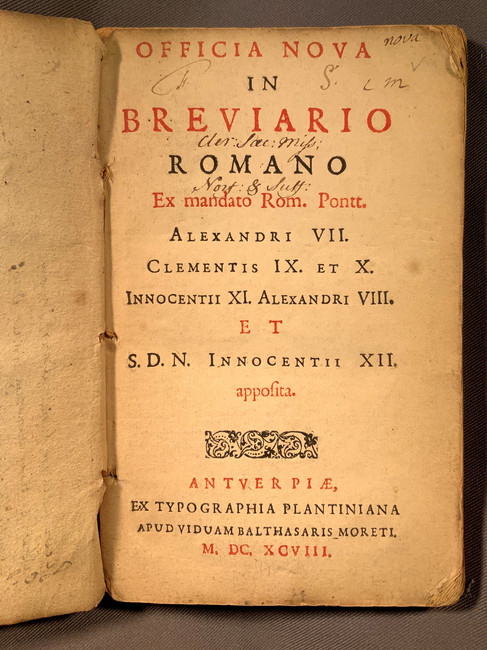

L-R: Widow of John Moretus, 1615; Widow of Balthasar Moretus, 1698

The Plantin Moretus family ran their publishing and print company for three centuries, from 1564 to 1867, when it became a museum and is now a UNESCO world heritage site. It was pre-eminently a family company, and women were as important as men within it. Much of the longevity of the company was due to the competence of the women in successive generations of the family.

Christophe Plantin started the Plantin Press, and with his wife Joanna Riviere had 5 daughters and a son. All his daughters were literate in Greek and Latin as well as vernacular languages, and worked in the company, heading up different parts of it – Margaretha and her husband ran the Leiden branch, for instance. Martina Plantin ran the silk workshop and business from the age of 17, and later married Jan Moretus and had 10 children with him. After Jan died in 1610 Martina was head of the firm until handing over the reins to her 2 sons, Jan and Balthasar.

It was Martina and her sons who were the printers of our book A/135 in 1615. They are identified on the title page as ‘Viduam & Filios Ioannis Moreti’, ‘the widow and sons of John Moretus’.

The Plantin Press was characterised throughout the 17th century and into the eighteenth by women who were capable and competent. Martina’s grandson, also called Balthasar, married Anna Goos who took over the running of the company in 1673. She even travelled from Antwerp to Spain to sort out a financial crisis caused by the Hieronymite Fathers of San Lorenzo defaulting on their payment. She resolved contractual breaches and negotiated a repayment schedule. One of Anna’s sons, Balthasar III, married Anna Maria de Neuf, who ran the Plantin Press from 1696 to 1714.

It is Anna Maria who was the printer of our book A/138. On the title page she is identified as ‘Viduam Balthasaris Moreti’, ‘the widow of Balthazar Moretus’

Because the Plantin Moretus museum in Antwerp has preserved not only the building and all the printing equipment but also the business records, we know a lot about the women who ran the company alongside the men of the family, and who frequently ran it alone. This level of detail is not available for other printing establishments.

Despite the lack of detail for the other women printers, some of the other women are also traceable even if we do not know their names. Two of the books, A/39 and A/238 were printed by the widow of Nicolas Courant. Both books were published in 1633. The Courant family were based in Rouen – which is where Robert Persons SJ had set up a printing press after he left England. The printing business was established by Pierre Courant in about 1570. His sister married another printer in Rouen, Jean Clou, who was elected a master printer in 1579. Pierre was father of Nicolas, and of Julien, both of whom went into the family printing business, and uncle to Pierre Philippe who was also printer at Rouen and later at Caen, who printed an English Bible. The Courant printing firm was involved in many works for whose publication the English Jesuits were responsible. We know that Nicolas Courant died either in late 1630 or early 1631 and that for the next few years Nicolas’ widow ran the business. Both books in the Jesuit collection printed by her were printed in 1633. By analogy with Officiana Plantiniana we can suppose that the women in this family were involved in running the business throughout its existence. The printing networks were strengthened by the women like Pierre Courant’s sister who married Jean Clou, and the business was strengthened by women who could and did take over the reins like Nicolas’ widow who printed these books. Undoubtedly there were other women in the Courant family who were also involved in the printing business.

The widow of Mark Wyon is named as the printer of A/143 and A/162. Mark Wyon was a printer and publisher and bookseller who was born in Douai and set up his business there sometime before 1609. He mainly printed books in Latin by and for professors at the local university and local clergy, largely philosophy, theology and law. He printed a few books for the English College in Douai, which had been established by the Jesuits in 1593. Mark Wyon died in 1630 and his widow took over. She ran the business for nearly 30 years, until 1659. Under her leadership the type of book printed by the company changed. A much larger proportion of the books she printed were in English or French than they had been when her husband was alive. The English books were aimed at English Catholics and were written or translated by professors at the English College. This is the case with both of the books printed by her in the Jesuit collection – A/162 says on the title page that it was translated into English by M.C.P. of the English College at Doway, M.C.P. being Miles Pinkney, who also went by the name of Thomas Carre, and was based at the English College from 1625-1634. Widow Wyon was a business-like printer, who supplied plain books for a market which consisted of impoverished scholars who could not afford lavish books. Like the example of Mary Thompson, here again we see evidence of a woman making her own business decisions.

The widow of Charles Boscard, whose name was Jeanne Buree, printed A/53 in St Omer in 1630. Charles Boscard was one of a small number of printers in St Omer in the early 17th century and his output included Catholic material aimed at the English market, driven by the establishment of the Jesuit school in St Omers by Robert Persons SJ in 1593. Much of the Jesuit material was printed by the English College Press itself, set up in the school for just this purpose. But local printers, including the Boscards, got work from this source too, despite complaints from the English readership about errors creeping in due to non-English speaking printers. Charles Boscard died in 1630, and Jeanne Buree printed books for at least 9 years after his death, identifying herself on title pages as the ‘Widow of Charles Boscard’.

Less is known about the other women who are identified as printers in the Jesuit books, but there are inferences that we might be able to draw. Like the women of the Officiana Plantiniana, it is likely that they were partners in the business throughout the time the business was in place. We can also assume they were astute business women as they appear to have handed their businesses on to the next generation as going concerns.

This brief survey of women printers whose books have ended up in the Jesuit Archive’s collection in London is based on only 200 of the nearly 1000 books, so doubtless there will be more to come – watch this space!

Comments